Wing On and Co. Ltd.,Ultimo Road and Quay Street

Yocksui Bros. 4 Ultimo Rd

Hop Lee & Co

W. Mow Sang & Co

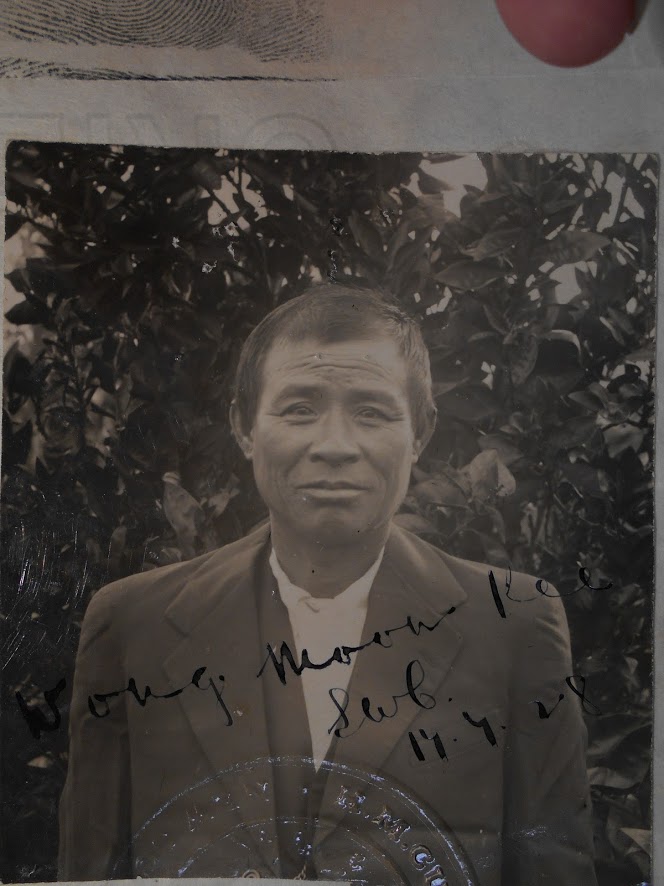

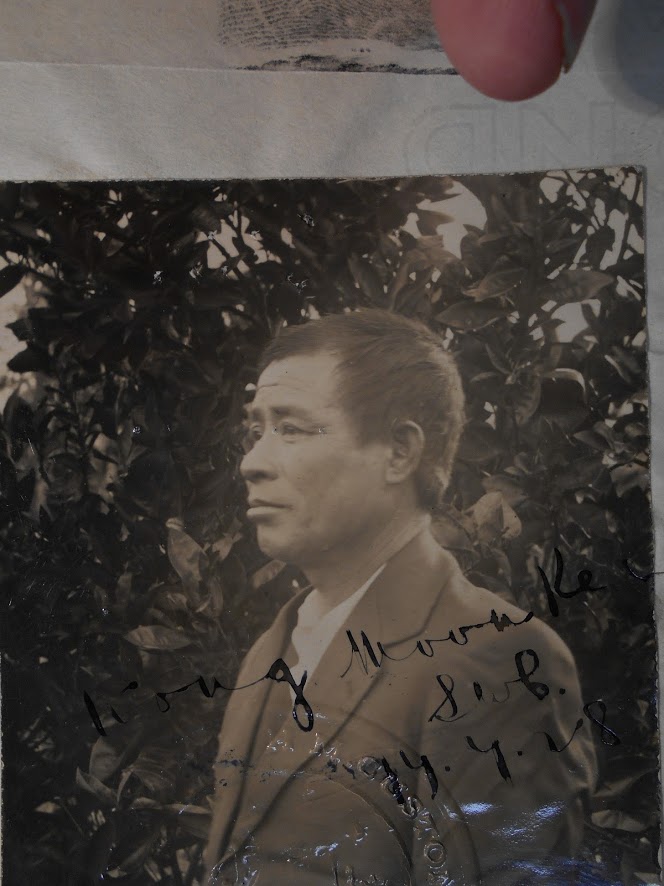

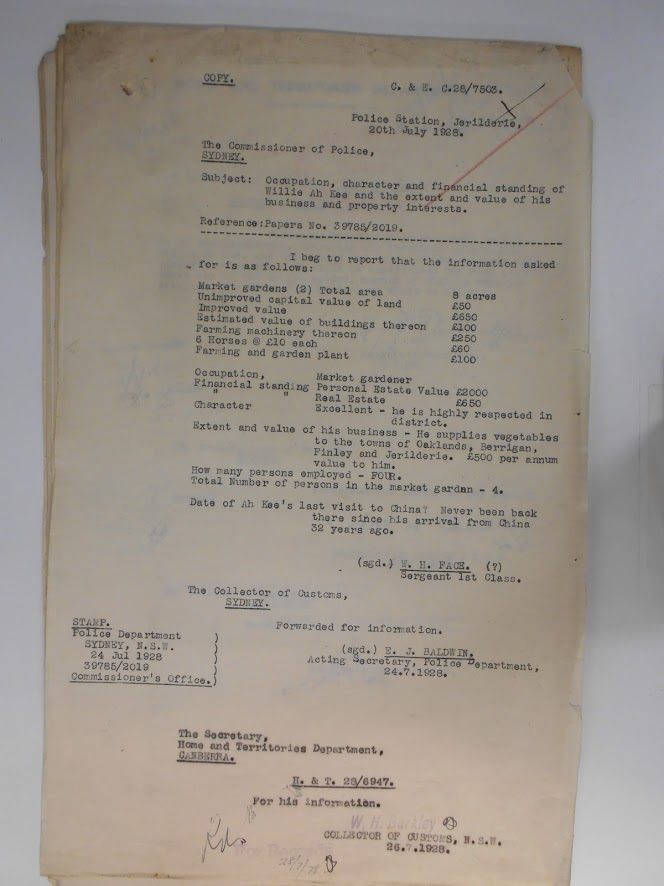

SP42.1C1928.7485 Wong Moon Kee OR Won Mon Kee b.Canton 19.11.1875 Gardener at Hop Sing Gardens Jewrilderie arrived 1897

R. White re Introduction of Chinese to grow bananas on Tweed River N.S.W

Chinese in Banana Industry.Contents range1919 - 1920Series numberA1Control symbol1920/5209

NAA: A1, 1920/5209

Sun Tiy Sang Delivery Truck c1920

Chinese dominated the production and distribution of fruit and vegetables in N.S.W. and the other colonies.

Even with the prohibition of owning land, some gardeners rose from small farm workers, usually in co-operative syndicates with other country men, to selling door-to-door, running a market stall, and eventually becoming partners in larger firms such as Wing On and Co which distributed interstate and eventually overseas with branches in mainland China.

Chinese established the Banana, Pineapple and Sugar Cane Industry. Production and distribution was based on clans, along the east coast of Australia. For example, the Yip clan farmed and distributed bananas from Cairns and Geraldton (Innisfail) down to the Sydney and Melbourne Markets.

Notes

Sugar cane first arrived in Australia on the First Fleet in 1788 and was originally planted in Norfolk Island. The first Australian sugar plantation and mill was established at Port Macquarie in 1821 but was abandoned nine years later. Colonial authorities and settlers then turned their attention to southern Queensland, northern New South Wales and the Northern Territory as potential sites for successful cane-growing.

Due to strong opposition towards the hiring of non-European labour, white workers dominated the sugar industry in New South Wales. Chinese labour, however, was vital to cane-growing ventures in the Northern Territory and Queensland. The Northern Territory entered the sugar market in the 1880s. The Delissaville, Daly River and Shoal Bay sugar plantations relied on Chinese workers but they closed due to poor soil and/or lack of financial assistance. Chinese farmers also grew sugar cane on small parcels of land around Darwin.

Chinese migrants were particularly central to the production of sugar in the Cairns district. In fact, they were the first to grow sugar cane in Cairns on a commercial basis. One of the town's well-known sugar businesses was the Hop Wah plantation. Established in 1878 by Chinese businessman Andrew Leon, Hop Wah was an entirely Chinese co-operative with the exception of one European engineer. The plantation, like many others along the Queensland coast, was not able to survive the drop in world sugar prices in the early 1880s and was forced to close in 1885.

As sugar declined in the mid-1880s, bananas became the major Chinese export crop in Cairns. Chinese involvement in the sugar industry returned after the ratification of the Sugar Works Guarantee Act in 1893. The Act allowed landholders to receive financial assistance from the government to set up central mills supplied by small farmers without restrictions on the type of labour employed. As a result, the plantation mills began to lease their land to small farmers, including the Chinese.

Although racial hostility and later discriminatory practices hindered the success of Chinese cane farmers, Chinese sugar producers in Cairns flourished into the early 1900s. The town of Aloomba in particular became a hub for the Chinese sugar industry and produced several prominent cane farmers, including Kwok Yin-Ming (also known as Willie Ming), Ah Tong, Ah Lin and Wong Fong.

From 1906 Chinese farmers began to withdraw from Queensland's sugar industry for several reasons. Firstly, Pacific Islanders were being deported from Queensland, thereby depriving Chinese farmers of their main source of labour. Chinese growers were also excluded from receiving a bonus for cane which had been grown with European labour. Chinese involvement in Queensland's sugar industry was also affected by extra charges placed on cane grown by Chinese farmers, a reluctance by major sugar mills to lease land to the Chinese and a cyclone which devastated farmers in 1906 and 1907. Only a few Chinese farmers remained active in the sugar industry in the 1910s.

Sources used to compile this entry: May, Cathie R., Topsawyers: The Chinese in Cairns, 1870-1920, James Cook University, History Department, Queensland, 1984; May, Cathie, 'The Chinese in Cairns and Atherton: Contrasting studies in race relations, 1876-1920', in P. Macgregor (ed.), Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, Museum of Chinese Australian History, Melbourne, 1995, pp. 47-58; 'A Trip to Delissaville - By a Traveller', Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 21 January 1882, p.2-3; 'The Northern Territory', South Australian Register, 15 March 1884, p.1s; 'Mr Brandt's Shoal Bay Sugar Plantation', North Australian, 7 August 1885, p.3; Griggs, Peter D, Global Industry, Local Innovation: The History of Cane Sugar Production in Australia, 1820-1995, Peter Lang, Bern, 2011; Wills, Joanna, 'Remembering the Cane: Conserving the Sugar Legacy of Far North Queensland', Paper given at the Professional Historians Association (Queensland) conference held on 3-4 September 2009 at Brisbane.

Prepared by: Snjezana Cosic

As mining became less profitable in the various colonies from the 1870s onwards, market gardening became the next most common Chinese occupation. At this time European Australians avoided market gardening which provided a niche for the many Chinese in Australia with agricultural backgrounds. By the 1900s approximately one third of all Chinese in Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia were engaged in market gardening. Even before this Chinese on the gold fields grew their own vegetables and those in market gardening at this time possibly made more money than those mining gold.

Market gardens tended to be located in the city suburbs. Chinese communities, like the one in Alexandra, Sydney, often grew up around them. In Melbourne there were market gardens along Merri Creek and in suburbs such as Brighton and Caulfield. In Western Australia they tended to be around Perth and in Fremantle along the Swan River. In the Northern Territory the Chinese grew the bulk of fresh produce for Darwin on the outskirts of town and in the Pine Creek area. In north Queensland Chinese market gardening was really more on the scale of farming with Chinese specialising in bananas and sugar and even experimenting with rice, corn and lychees.

Chinese market gardens tended to operate on a cooperative basis with as many as ten workers, often from the same clan. There were close ties between market garden cooperatives and urban Chinese storekeepers and greengrocers who helped provide gardeners with credit or financial support. Using hand made tools market gardeners worked long hours in this very labour intensive industry. Crop rotation and double cropping methods were used to grow a range of produce including tomatoes, cauliflower, herbs, leafy vegetables like lettuces. Produce was sold either direct to the market or else through a commission agent who sold the produce on the gardeners' behalf. Although Chinese market gardeners and hawkers are seen as synonymous, due to the high labour intensity of both activities it is unlikely that an individual could perform both concurrently.

As in other industries where the Chinese were successful, Chinese market gardeners also faced opposition from their European counterparts. In 1900 a Market Gardeners' Association was formed partly in opposition to Chinese competition. During the depression others resented the fact that the Chinese were able to make money out of 'incidental' crops which non-Chinese found uneconomical. Chinese market gardeners were accused of using urine and faeces to fertilise their gardens and of living in insanitary conditions.

As the Chinese population in Australia declined so too did Chinese market gardeners. The Greek and Italian community started to move into the industry, particularly after World War II. However it was not until at least the 1950s, possibly later, when the last of the original Chinese market gardens finally disappeared.

Sources used to compile this entry: Bate, Weston, A History of Brighton, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1983; Broome, Richard, Coburg: Between Two Creeks, Lothian Publishing, Melbourne, 1987; Chou, Bon-wai, 'The sojourning attitude and the economic decline of Chinese society in Victoria, 1860s-1930s', in P. Macgregor (ed.), Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, Museum of Chinese Australian History, Melbourne, 1995, pp. 59-74; Cronin, Kathryn, Colonial Casualties: Chinese in Early Victoria, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1982; Fitzgerald, Shirley, Red Tape and Gold Scissors [Chinese language version.], 1996; Fitzgerald, Shirley, Red Tape and Gold Scissors: The Story of Sydney's Chinese, State Library of NSW Press, Sydney, 1996; Ryan, Jan, Ancestors: Chinese in Colonial Australia, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 1995; Shun Wah, Annette & Aitkin, Greg, Banquet: Ten Courses to Harmony, Doubleday, Sydney, 1999.

Prepared by: Sophie Couchman, La Trobe University

Although bananas have been grown in Australia since the 1830s they were not commercially produced until the 1880s when crops from Queensland were transported south. Chinese played a dominant role in both the growing and importation of bananas across Australia until the 1930s and continue to be active in the area today.

The quick turn over of the banana crop which could be harvested continually once it reached maturity made it an ideal crop for many sojourning Chinese. Queensland was the main supplier of bananas in Australia. The Cairns and Geraldton (Innisfail from 1909) districts were particularly suited to banana growing. Much of the land in these areas was cleared by Chinese banana growers due to the practice of clearing new land to plant new crops rather than replanting areas that had been already cleared. The early prosperity and survival of the Cairns and Innisfail area has been directly attributed to the success of the Chinese in the banana industry. Both Chinese and non-Chinese businesses in these towns developed to provide goods and services to Chinese banana growers. Chinese merchants in particular played in important role as commission agents and assisting growers with finance.

The move into banana wholesaling and distribution appears to have been a natural extension of the dominance of Chinese growers. It was common for commission agents to negotiate between the growers and city wholesale merchants. A number of large Chinese wholesale fruit merchants formed in both Sydney and Melbourne at the beginning of the century and profited from Chinese involvement in banana growing. A number were very successful. Chinese merchants held over half of the banana trade in both Sydney and Melbourne in the 1900s and also distributed fruit to country towns. Fruit merchants replaced storekeepers and grocers as the new merchant elite within the Chinese community. Capital from fruit merchant firms was used in the establishment of a number of the largest department stores in Hong Kong, Canton and Shanghai and in the formation of the China-Australia Mail Steamship Line.

By the 1930s Chinese dominance in both growing and wholesaling of bananas had dissipated. In Queensland the older banana growers were returning the China and the younger Chinese in the area found sugar cane to be a more reliable crop. In the first decade of the century the wholesale of Queensland bananas had been unfavourably affected by fruit fly contamination, severe cyclones, delays due to World War I, poor transportation and competition from Fijian bananas which were considered to be a better banana. There was also a limit placed on the amount of land that could be leased by Chinese to grow bananas and incentives for 'white' growers to enter the industry.

When supplies of Queensland bananas were unreliable some Chinese merchants in Melbourne and Sydney survived this through diversification into other markets and fruits. Some began importing Fijian bananas and some even established their own plantations in Fiji. However the introduction of increasing tariff duties between 1911 and 1920 on Fijian bananas eventually made them unprofitable. During World War I a number of Chinese merchants from Sydney also began purchasing land in the Tweed River area of northern NSW for banana growing. After the war returned soldiers also began purchasing land there with the resulting competition leading to discontent and eventually anti-Chinese race riots in 1919. Chinese merchants in Sydney and the Chinese Consul-General tried to dampen racial animosity. A devistating outbreak of 'bunchy top' virus severely set back the fledgely banana industry in NSW quelling racial tensions. In Queensland the government was also concerned developing a 'white' banana industry. In 1921 they passed the Banana Industry Preservation Bill designed to prevent coloured labour, including Chinese labour from entering the industry without passing a 50-word dictation test in any prescribed language directed by the Secretary for Agriculture.

In Melbourne in the 1880s the majority of Chinese banana merchants established their businesses and ripening rooms in Little Bourke Street. Bananas arrived at the wharfs where they were loaded onto horse-drawn open lorries and transported to ripening rooms in Little Bourke Street. Bananas were ripened in special rooms that were heated with a mix of raw gas and ethylene. From Little Bourke Street bananas were taken to the major wholesale or retail markets for sale. After 1930 Chinese banana merchant firms began to diversify into fruit and vegetable merchants or close their business. The fruit and vegetable wholesale industry became centralised at the Queen Victoria Market and banana storage and ripening rooms moved to the new market and out of Melbourne's Chinatown.

Sources used to compile this entry: Blake, Alison, 'Melbourne's Chinatown: The evolution of an inner ethnic quarter', BA (hons) Thesis, Department of Geography, University of Melbourne, 1975; Bolton, G. C., A Thousand Miles Away: A History of North Queensland to 1920, ANU Press, Australian Capital Territory, 1970; Couchman, Sophie, 'The banana trade: Its importance to Melbourne's Chinese and Little Bourke Street, 1880s-1930s', in P. Macgregor (ed.), Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, Museum of Chinese Australian History, Melbourne, 1995, pp. 75-90; Couchman, Sophie, 'Tong Yun Gai (Street of the Chinese): Investigating patterns of work and social life in Melbourne's Chinatown 1900-1920', MA thesis, School of Historical Studies, Monash University, 2001; Loading bananas in Innisfail, c1900 [Photograph], Date: c. 1900 Place: Australia - Queensland - Innisfail (Geraldton); May, Cathie R., Topsawyers: The Chinese in Cairns, 1870-1920, James Cook University, History Department, Queensland, 1984; Yong, C. F., 'The banana trade and the Chinese in NSW and Victoria, 1901-1921', ANU Historical Journal, vol. 1, no. 2, 1964, pp. 28-35; Yong, C.F., New Gold Mountain: The Chinese in Australia 1901-1920, Raphael Arts, South Australia, 1977.

Prepared by: Sophie Couchman, La Trobe University

From peasant farmer to garden operator

From gardener to hawker to dealer

"From Shekki to Sydney", Stan Hunt OAM talks about his early upbringing in China, his immigration to Sydney, and the establishment of a series of successful family businesses.

From hawker to market agent

From market dealer to large trader

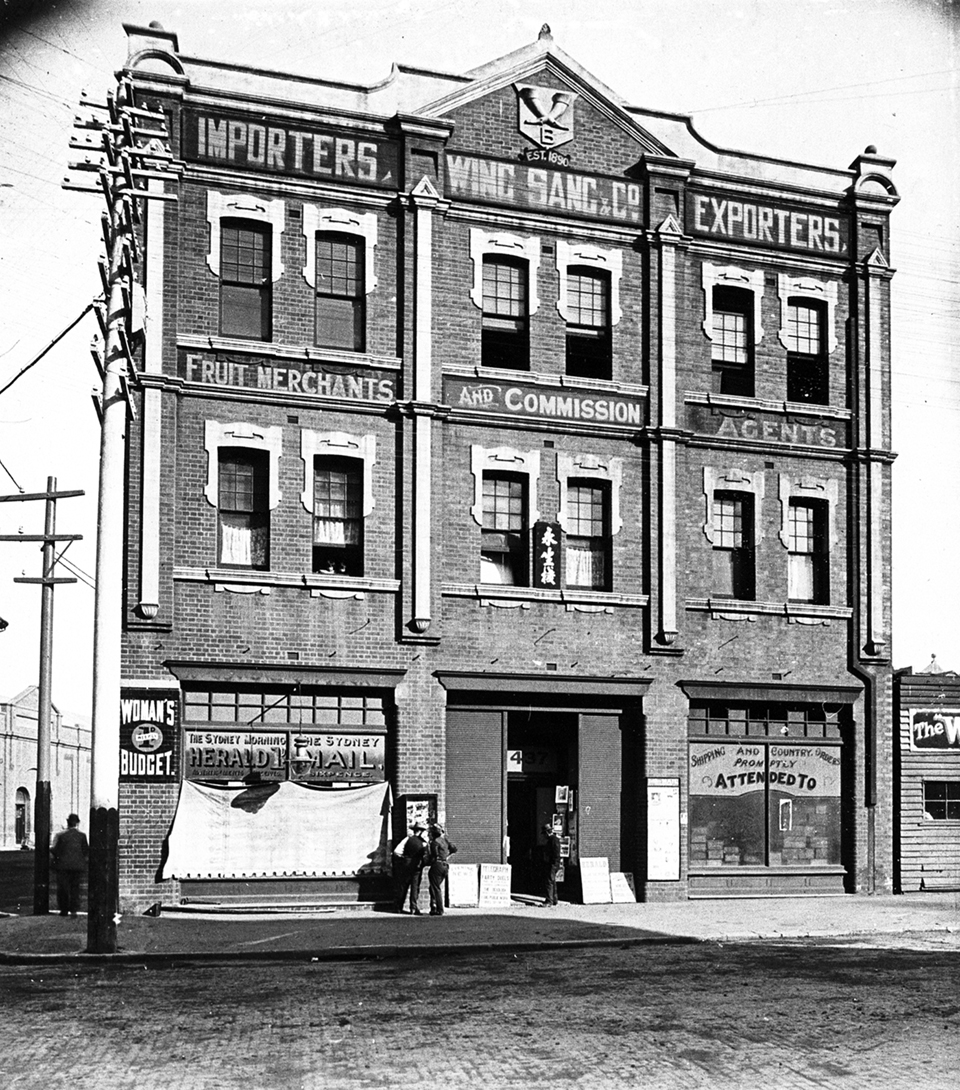

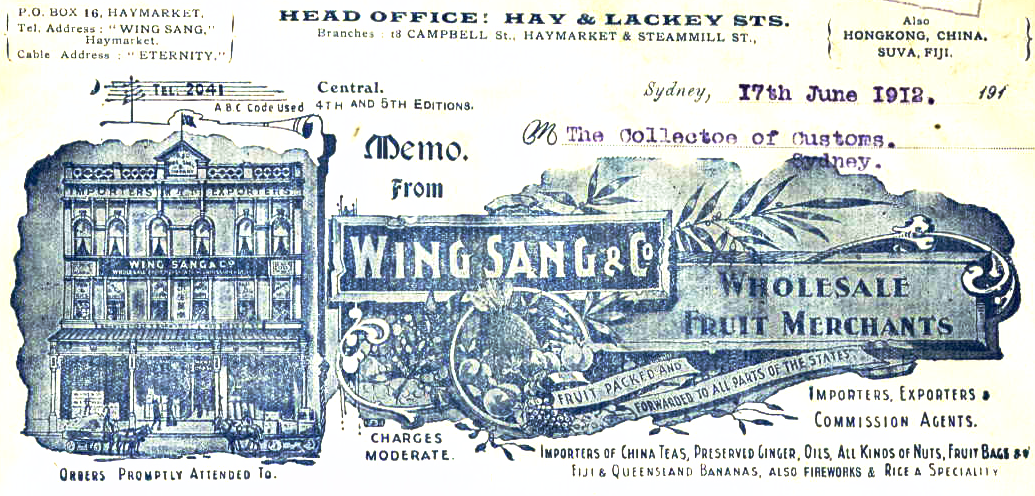

Wing Sang & Co Haymarket c1909

Wing Sang, for example, began tra

Wing Sang, for example, began tra ding Fijian bananas into Sydney's

markets in the 1890s, and eventually established a department store,

allegedly along the lines of Sydney's Anthony Hordern's,

in Hong Kong in 1900. Branches in Canton and Shanghai followed, and by

the 1960s, the Wing Sang Company was involved in banking, hotels and

various manufacturing enterprises. The Wing On firm similarly grew out

of fruit trading in the Haymarket to become a multi-faceted business

empire.

ding Fijian bananas into Sydney's

markets in the 1890s, and eventually established a department store,

allegedly along the lines of Sydney's Anthony Hordern's,

in Hong Kong in 1900. Branches in Canton and Shanghai followed, and by

the 1960s, the Wing Sang Company was involved in banking, hotels and

various manufacturing enterprises. The Wing On firm similarly grew out

of fruit trading in the Haymarket to become a multi-faceted business

empire.

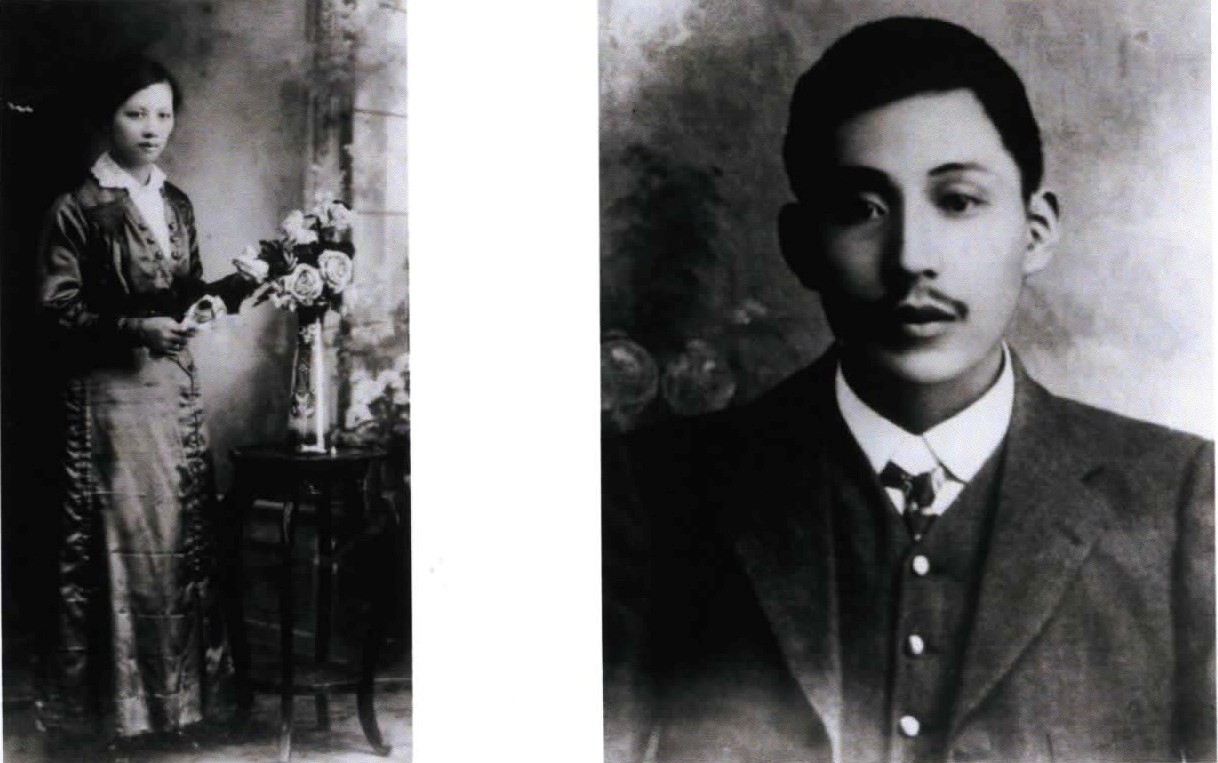

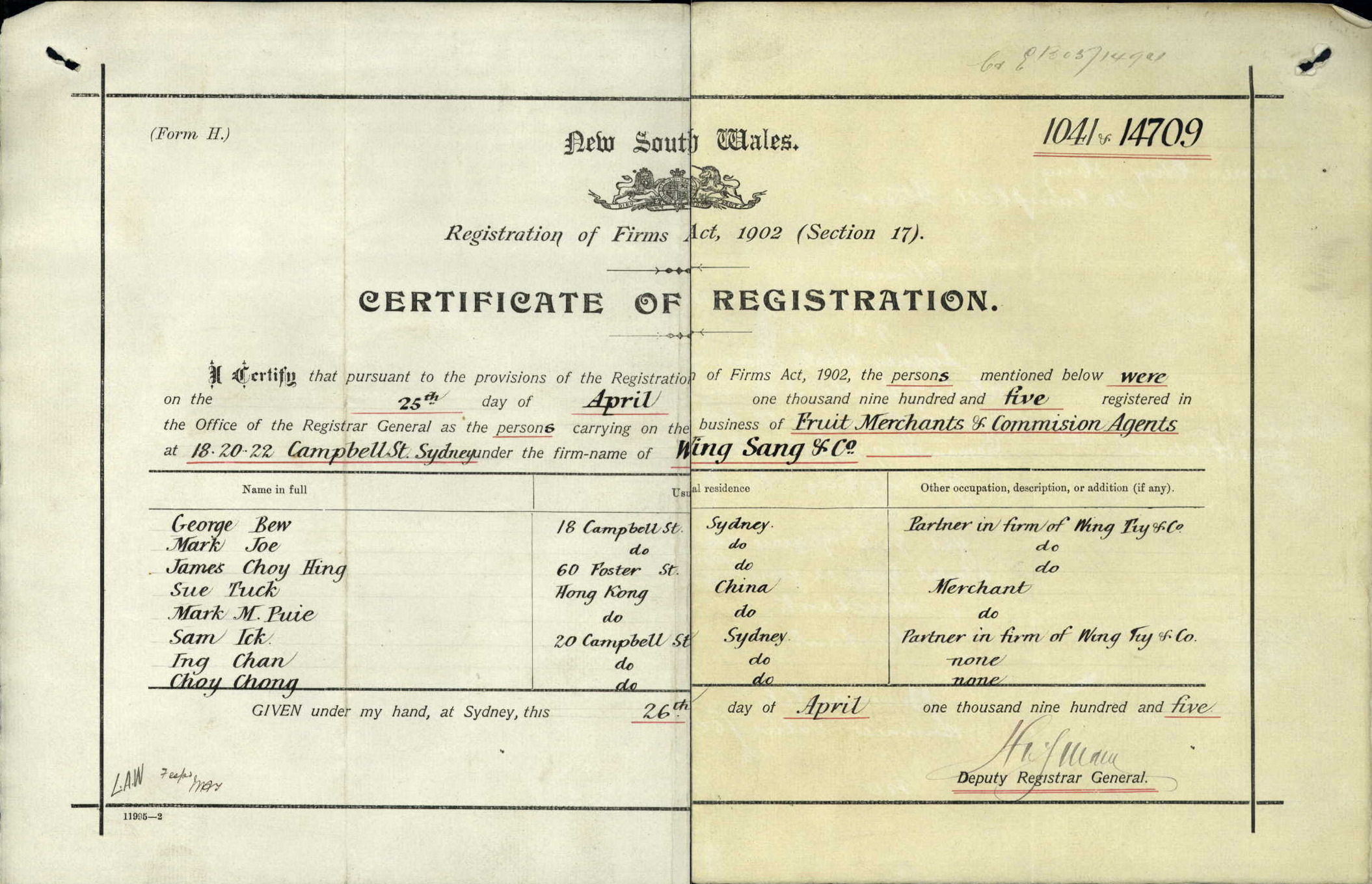

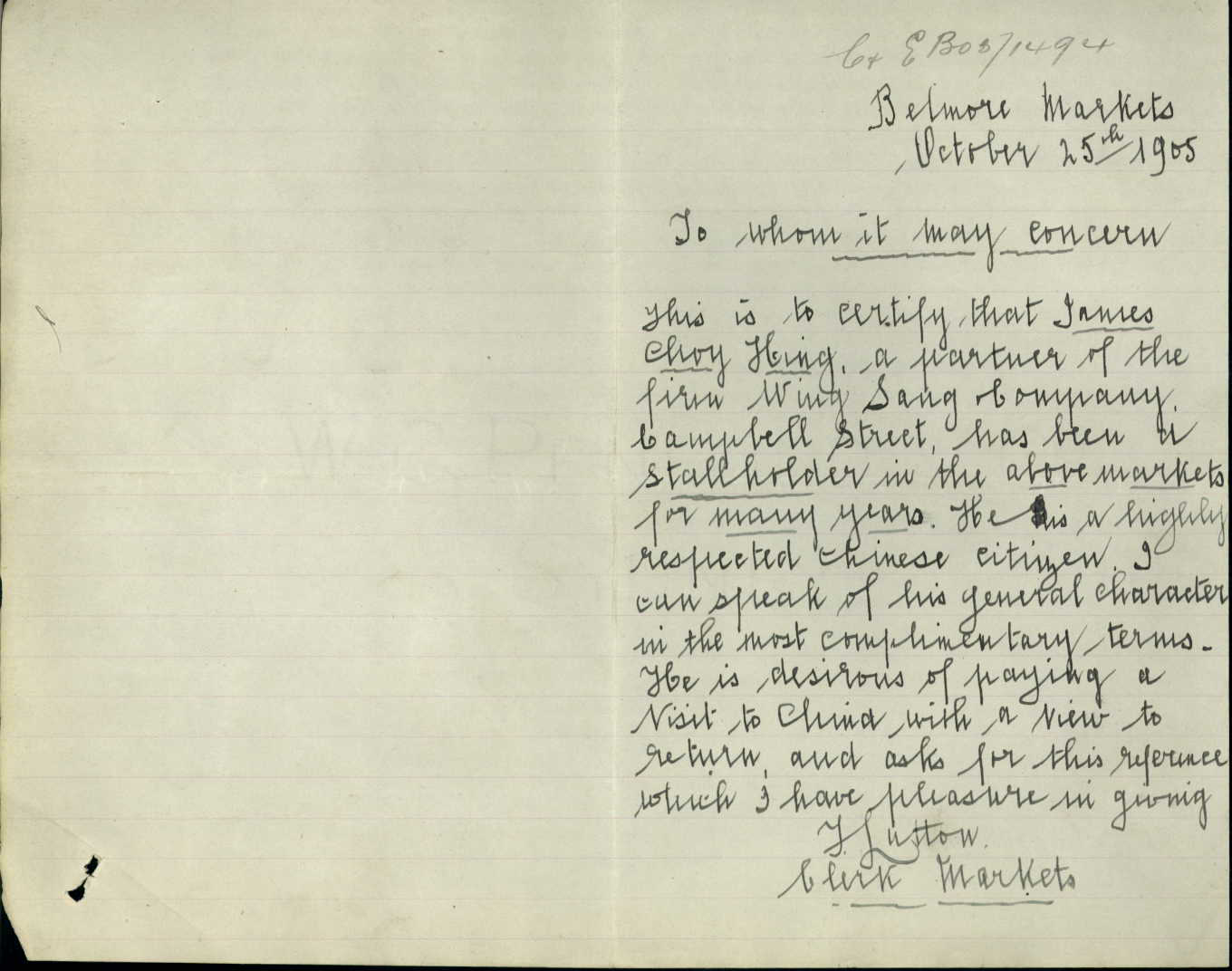

Kwok Bew (aka George Bew) was born in 1868 near Canton China and after the death of his father, Kwok left for NSW in 1883, working as a door-to-door salesman at Grafton and later as a produce merchant in Sydney. He married Darling Young a daughter of a Bourke merchant in 1896 at the Presbyterian Chinese Church in Sydney.

His Wing Sang & Co. expanded from general produce into a marketing agent for fruit and vegetables supplied by Chinese gardeners in Northern NSW, Queensland and the Pacific region. The company grew quickly and he soon managed to control the wholesale banana market in NSW and Queensland. In 1900 he started to import bananas from Fiji. In the early 1900's he founded the Wing On & Co., an expanding commercial conglomerate.

He emerged as a Chinese business leader of considerable influence, and he played a leading role in the formation of the China-Australia Mail Steamship Line in 1917. He had become active in Chinese-Australia politics as vice-president of the Chinese Merchants’ Defence Association, formed to counter the propaganda of ‘White Australia’ merchants. He helped to establish the Chinese Republic News in Sydney, which circulated extensively in Australasia, the South Pacific, Strait Settlements, Hong Kong and China itself.

Late in 1917 he returned to China and founded the Wing On emporium in Shanghai, which specialized in quality local and imported goods and it became the largest department store in China. By the early 1920's he expanded into banking, retail and manufacturing located in the foreign concessions in Shanghai and Canton. He died in 1932 in Shanghai, survived by his wife, 4 sons and 4 daughters. At his death he was a director of the Chinese Government Mint and managing director of the Wing On Co. Ltd.