Banner Image: Ah Kim with his wife Lily (a Gajerong woman) and family, photographed in 1918 in their Muggs Lagoon market garden

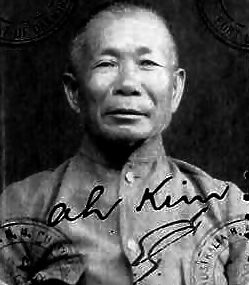

An Aboriginal Chinese family: the Ah Kims

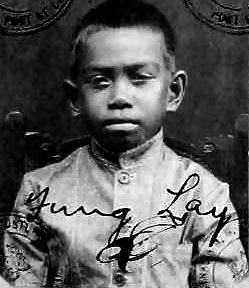

Ah Kim was only eleven when he left Hong Kong for the Northern Territory in 1872 to join clan in Darwin. He worked there for 24 years,market gardenering and cooking. He settled at Muggs Lagoon (between Wyndham and Kununurra in the Kimberleys, Western Australia) where he worked a market garden and married a local woman, Inje or Lily, in 1908. They had 3 boys and 3 girls.children. He sent the eldest sons, Tyson and Toon Cho, to be educated to Hong Kong. He accompanied Fung Lay there when he was 60tfor schooling.Fung Lay and Tyson were later killed in a 'Boxer Uprising' there. Toon Choi (George) returned home in 1928.

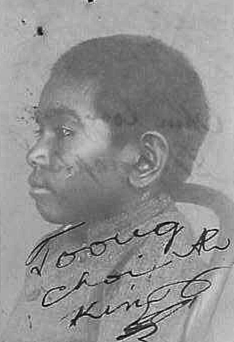

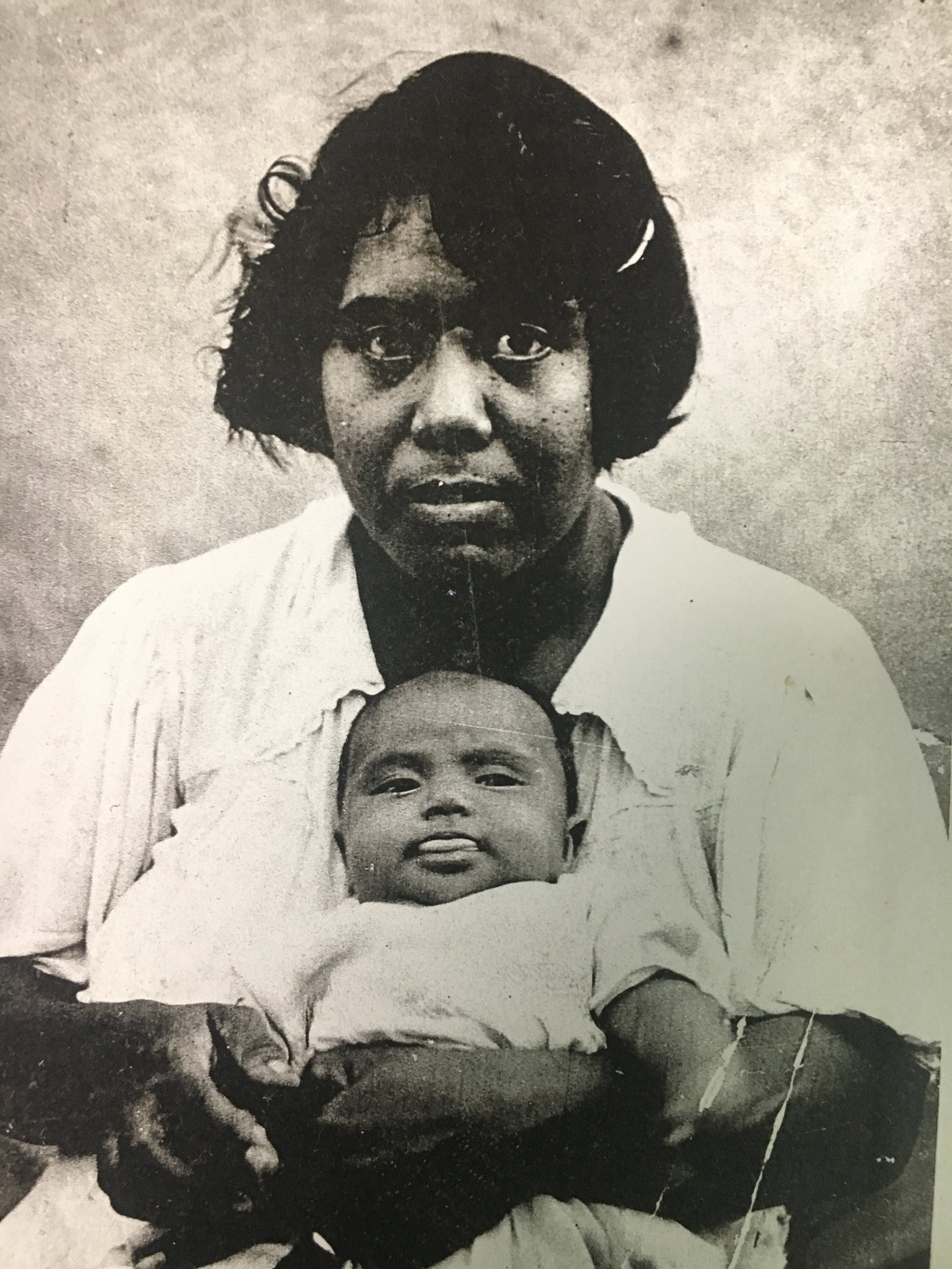

The 3 girls, Lemon (Lemmie),Orange (Orrie) and Winnie were all taken away from Ah Kim after their mother died. He had cared for them on his own until the Aborigines Department found out about them. They were sent to the half-caste native settlement at Moore River. He never saw them again.

In 1959, 99 year old Ah Kim wanted to be buried in his garden at Muggs Lagoon, so he dug his own grave, laid down in it and waited for death.

George or Toong Choi Ah Kim c1928 Wyndham

George or Toong Choi Ah Kim c1928 Wyndham

Winnie Orange

Orange

Lemon

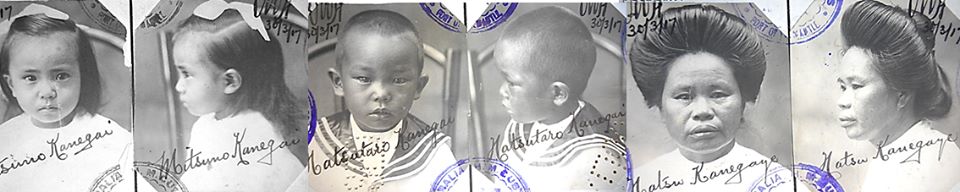

An Aboriginal Japanese: the Kanegaes

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet written by me:

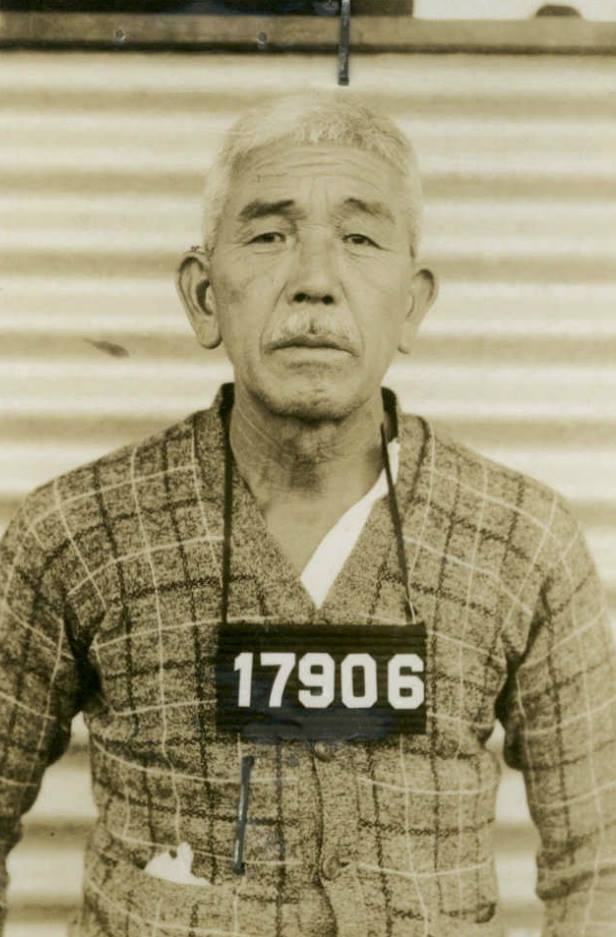

Rare preserved photograph from the World War 2 internment camps:

Matsumoto Kanegae, formerly a Broome shopkeeper, in 1942

The Outsider W ithin p.119: “The Ab

ithin p.119: “The Ab original wives of Japanese men — who by law took on foreign nationality upon their marriage — were interned with their husbands and mixed-race children. In some cases this meant that shared businesses that had been left behind failed. Christine Choo reports that one Aboriginal woman interned with her husband was Lydia Kanagae, who had been married to Matsumoto Kanagae for 25 years. Matsumoto's request that his wife be released from internment so that she could continue to run their shop was denied.

original wives of Japanese men — who by law took on foreign nationality upon their marriage — were interned with their husbands and mixed-race children. In some cases this meant that shared businesses that had been left behind failed. Christine Choo reports that one Aboriginal woman interned with her husband was Lydia Kanagae, who had been married to Matsumoto Kanagae for 25 years. Matsumoto's request that his wife be released from internment so that she could continue to run their shop was denied.

Unwanted Aliens by Yuriko Nagata on p.74 to "Yoshi Kanagae, an Australian-born of Japanese-Aboriginal origin, was neither upset nor afraid of being arrested. She said: "Dad was in and Auntie was in...so I was excited to go looking forward to seeing them again." (interviewed Sydney, 22.8.1987 as Y. Nabeshima).

Yoshi's mother Lydia Kanagae was a Djugun woman from Broome cousin sister of Cecelia Nanagon. Lydia's sons were George aka Ingee, Mitsu, Yoshi, Subu & Hudsu who drowned at Cable Beach while young. The entire family were interned at Cowra NSW. Both George & Mitsu were sent to Japan. George returned after Hiroshima & later died in Derby. It is unknown what became of Mitsu. Yoshi was living in Greenacre (Sydney) & Subu return to Broome along with Hudsu after release from internment. Lulu George was strong in his Cultural knowledge for Djugun country (Boome) & apparently both he & his sister spoke fluent Djugun prior to being sent to Japan. George was placed in the Japanese Army school which grieved him no end as he had no desire to raise arms against Aust. Fortunately it didn't happen & he briefly worked in ship building in Nagasaki before returning home.George "Yengiro Kanagae was 9 when this photo was taken. He left Broome on 25.2.1935 and was a school boy in Nagasaki when Japan entered the War. He later worked in an engineering work shop and was 20 when the War ended. His father, Matsumoto, asked the manager at Streeter and Male to represent him in his request to have his eldest son return to Broome. Permission was granted by Customs for his return in 1949 when he was 24

Five members of the Kanegae family were arrested in Broome on 8.12.1941 immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbour and the USA declaration of war against Japan:

Hatsu (b. Nagasaki, 9.9.1876) was 64 when arrested. She was a widow, and worked as a boarding-house keeper. She was repatriated to Japan, leaving from Melbourne on 21.2.1946. Her younger brother,

Matsutaro (b. Nagasaki, 17.3.1876) was 62. He arrived in Broome on 15.9.1897 as a 19 year old. At the time of arrest he was a storekeeper. He married Lydia (b. June 1893) who was 47 when she was sent to Tatura internment camp in Victoria with her husband, sister-in law and 2 children:

Shizuyo (b. Broome 8.9. 1918) was a 23 year old housekeeper and eldest sister to

Saburo (b. Broome 4.5.1934) was 6 years old when he joined the other Aboriginal-Japanese at Tatura.

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

An Aboriginal, Phillipino and Japanese family: the Matsumotos

Kakio Matsumoto

Tomoko Irlean Matsumoto was four years old when her father was taken to the camp in Tatura.

Tomoko Irlean Matsumoto was intitially interned at Tatura, but was later seperated from her parents.

Irlean’s father was Japanese and her mother was Aboriginal. While her and her siblings initially went with their father to Tatura, they were later separated from their parents and sent to a Christian Mission in the Tiwi Islands, along with members of the Stolen Generations.

“I was still confused (at that time), still a bit traumatised about being separated from our parents,” Ms Matsumoto

“But mainly I remember the picnic days, when the older girls used to take us out picnicking.”

“Mary Ellenor (Lena) Corpus was born in Broome in 1907. Her mother, Maria Emma Ngobing, was an Aboriginal woman and her Father, Sibero Corpus, was Filipino…

In 1935 Lena was questioned about a constant visitor to the house, a Japanese indentured crewman, Matsumoto Kaiko. It was alleged that he was living with Lena, a charge she denied. Subsequently, Matsumoto left Broome for Darwin, and soon after Lena followed him there…In June (1938) a marriage was celebrated in Darwin between Matsumoto and Helen Barbara Corpus who was the same Lena Corpus.”

“The Commissioner of Native Affairs in Western Australia, in a letter to the Deputy Director of Security in Perth dated 30 June 1943, wrote:

‘A serious view is taken in this State regarding illicit (illegal) association between native women and Asiatics, especially Japanese….such marriages are unwise for social and national reasons.’”

Following her separation from her husband, Lena's mental health deteriorated. She was incarcerated without her husband and had sole responsibility for caring for their four young children. Lena had no control over her family's living arrangements and did not know when they would be released. She had little in common with the Japanese internee, and reSpOnSIDIffly toy caring tor incur tour young WHIM). Lena naU no control over her family's living arrangements and did not know when they would be released. She had little in common with the Japanese internees and could not speak their language. She did not know why she was being held and was forced to live far from her country and extended kin. Despite recommendations from medical officers and other authorities that Lena's mental health might improve if she were sent to Beagle Bay mission (where she could be reacquainted with Aboriginal friends and family). the Western Australian Deputy Director of Security did not permit her relocation. lie argued, instead, that from a security perspective her association with Japanese people, both before and after internment. should he regarded with suspicion. He went on to note that he objected in principle to the association of Asiatics and native women and urged that Lena and Kakio's case presented a good example of the inadvisability of such undesirable unions." The Commissioner of Native Affairs in Perth concurred, advising against her relocation to Beagle Bay mission due to her marriage to a Japanese person, and because 'she would be a menace to the safety of Australia if she were sent back to the Broome area'." It is hard to imagine how an Aboriginal mother of four could pose a security threat to the 'safety of Australia'. This paranoid response to Lena's desperate situation meant that she and her children were sent further away from her husband, to a Roman Catholic mission in Balaclava, South Australia. Suggestions that Kakio's status might be changed from prisoner of war to internee - enabling Lena and her children to be interned with him at a civilian camp - also fell on deaf cars. A further measure of the white Australian paranoia surrounding alliances between Aboriginal women and Japanese men concerns the chemical testing of Lena's letters to her husband. Lena's every move was scrutinised and restricted and, perhaps not surprisingly, her condition did not improve. In 1944 she was committed to a mental institution near Adelaide and her children were sent to a convent a further 200 miles away.

Tomoko Irlean Matsumoto's mother was Aboriginal Portuguese and she and her siblings were sent to a Christian mission.

Ms Matsumoto said her father, Kakio Matsumoto, built his life in Australia and it was his home.

“He was just a worker, lived and worked in Australia for so long and then get taken as a prisoner of war,” she said. “In a way I think that wasn’t fair.”

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

Broome: William Ishiguchi (son of Noboru), Maeda Yoshinori and Kuroda Toshio date unknown

The Ishiguichis

Number 2 Home: A Story of Japanese Pioneers in Australia by Noreen Jones

p.156 Mixed Marriages

Lynette lives in a Perth suburb. The oral history of her family background is important to Lynette and to her extended family, particularly the stories about her Aboriginal grandmother, Canice Topsy, a woman from Noonkanbah, near Fitzroy Crossing in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Australian records of her Japanese grandfather, Ishiguchi Noboru, are held in the National Archives, but the records do not tell the whole story. Lynette and her aunty Margaret, Noboru's daughter, have tried to discover what happened to him when he disappeared from his family in December 1941. Before beginning their search for him, they did not even know that he had been sent back to Japan after the war. They wonder where he died and where lie is buried. They do not know if he has another family in Japan or if there are unknown Japanese half-brothers and sisters living there.

Enquiries made in Japan on the family's behalf did not solve the mystery. Men from Noboru's home village who were interned with him in Australia knew of his Aboriginal wife and his Australian children and have photographs of Noboru's son among their snapshots of other Aboriginal people. They suggest that Noboru did not contact his family after his internment because of his wife's leprosy.

Japanese Husbands

Ishiguchi Noboru was horn in 1895 in the village of Uchiumi, Ehime prefecture, on the west coast of the large island of Shikoku. He arrived in Western Australia in 1913 as an indentured pearl diver(PIX 2) In September 1923 he married Canice in the Catholic church in Broome, having converted to Catholicism and been baptised 'James'. Noboru's eldest daughter, Margaret, recalls her father describing his narrow escape from death when his air line was fouled by a giant manta ray. The incident was later used by Ion Idriess in Forty Fathoms Deep, though in the book a whale was substituted for the manta ray. Margaret also remembers her tither making attempts to teach his children a few words of Japanese. In time, there were seven children to support and Noboru gained illicit additional employment bycooking at Iyo House, the boarding house operated by Mise Toyosaburo. Indentured crews were not permitted to take on shore work without special permission, and this was seldom given. Canice worked as a domestic in the house of Mr Gill, the school teacher in Broome. An undated memorandum titled 'Indentured labourers marrying or living with local women' from the Sub-Collector of Customs to Department of the Interior expressed the official attitude towards mixed relationships at that time:

Broome is acquiring an undesirable coloured population in which Malay, Japanese, Manila men and others are being intermixed with aboriginal. It is well known to anyone living in Broome that half caste girls are unobtainable for domestic services during the 'lay-up' season. Indents and local coloured are allowed to mix freely. Several cases of leprosy have been detected during the last twelve months.

The document went on to cite the case of Ishiguchi Noboro and Canice Topsy as an example.

also check out https://familysearch.org/wiki/en/Beginning_Japanese_Research

William Ishiguchi (right), the son of Ishiguchi Noboru, with Kuroda Toshio (left) and Maeda Yoshinori, Broome, undated. (Courtesy Sasaki Urmekichi)

He was imprisoned in more POW/Internment camps than most enemy aliens, but unfortunately little of his actual experience is revealed in the records. Like all other Broome divers and sailors he was reclassified from internee to POW because it was considered that their knowledge of the coastline would aid Japanese intelligence. They all were considered a greater security risk and sent to POW camps.

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

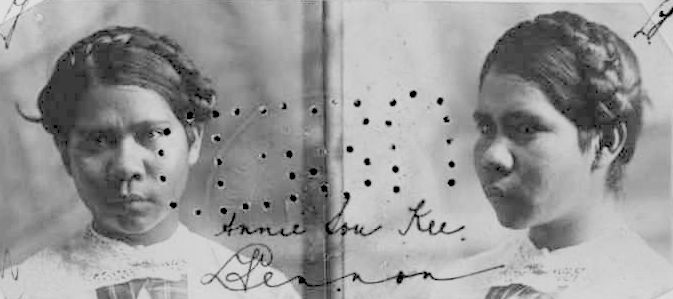

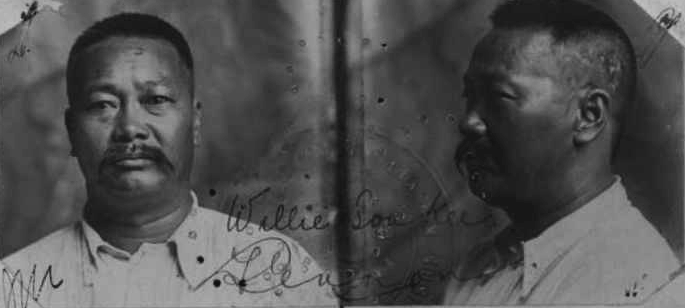

An Aboriginal Chinese family: the Sou Kees

Annie Sou Kee was born on Wondoola Station in North Queensland on 20 April 1895. In December 1916 she at worked Lawn Hill Station, near Burketown, as a cook's help to her husband, Willie Sou Kee. She left Australia permanently in 1917 with her son Tommy and they never returned to Australia

.Tommy Sou Kee was 4 months old in 1916 when he left for Hong Kong

.Tommy Sou Kee was 4 months old in 1916 when he left for Hong Kong Willie was born in Hong Kong on 27 July 1876, and worked as a cook and gardener at Lawn Hill. He traveled back and forth between Hong Kong and Australia on three occasions between 1916 and 1935

Willie was born in Hong Kong on 27 July 1876, and worked as a cook and gardener at Lawn Hill. He traveled back and forth between Hong Kong and Australia on three occasions between 1916 and 1935

– one of many Chinese men who travelled to the Gulf Country..jpg?timestamp=1558943804128)

Willie Sou Kee (pictured 1918) – one of many Chinese men who travelled to the Gulf Country

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

An Aboriginal, Chinese English family: the Ah Sam-Sibleys

Annie Sibley nee Ah Sam and her husband, George Patrick Sibley taken on Palm Island 1937.

Annie was the daughter of Tommy Ah Sam, a Chinaman who worked as a cook and gardener at Dunbar Station in far north Queensland. Here he met Maggie Croyden, an indigenous woman of the Kurdjan tribe. Tommy and Maggie’s daughter Annie Ah Sam ended up living with George Sibley at Mount Molloy, They had five children. George worked for a local saw mill and as a half-caste was paid directly by the mill. The law at the time dictated that Aborigines could only collect wages via the Chief Protector. George Patrick Sibley was the son of an Englishman and an aboriginal woman, making him a half-caste. He lived in the fringes of Mt. Molloy, Queensland with his family and worked as a lumberman. He was sent to the aboriginal penal colony, together with his wife and five children, for refusing to sign a work agreement (something he was not required to do). His arbitrary removal from his home was a result of the local authorities asserting their power over the indigenous people.

In Broome about 100 Japanese residents were arrested on the morning of 8 December. Miki Tsutsumi, secretary of the Nihonjin-kai in Broome, was one of them. He had come to Broome in 1921 as manager of the Tonan Shokai, a company which sold Japanese goods mainly to the Japanese community. He began writing a diary from the day of his arrest. His first entry reads: After I got up, I heard people were talking about Japan's attack on Hawaii and Malaya. I couldn't believe it ... At about 10.30, Inspector Lawson and three other policemen came and told us that we were to be taken to the gaol. They gave us a little time to pack up. At about 11.00 we got to the gaol ...

Hatsu Kanegae, who came to Broome in 1896 from Nagasaki, was one of the five single Japanese women arrested on the 8th December, 1941. Her niece, Yoshi, remembers the day her aunt was taken by the police:

I was at my auntie's house ... Auntie and I were washing and cleaning as we always did at that time of the day. It was about ten in the morning. We didn't know the war had broken out ... One policeman came and took her. He said, "I'm sorry but I have to arrest you." She packed a few things up and asked her neighbours to look after things...They were Filipino, good friends of hers.'

The policeman told us to pack up things, a change of clothes and things ... We were put in a tent at the Broome gaol. The gaol was already packed with the Japanese. We slept in the tent for one night and the next day we were taken on a ship ...69 Yoshi Kanegae, an Australian-born of Japanese-Aboriginal origin, was neither upset nor afraid of being arrested. She said: "Dad was in and Auntie was in ... so I was excited to go and looking forward to seeing them again."' At noon on 19 January the "Koolinda" left Broome carrying 212 Japanese internees, picked up thirty-four Japanese internees at Port Hedland, Point Samson, Onslow and Carnarvon, and arrived at Fremantle on 24 January. The internees were divided into two groups—the family groups being taken to Woodmans Point Internment Camp, and the men to Harvey Internment Camp. Harvey was about 100 kilometres south of Perth. The men arriving there were given a friendly welcome by Italian internees. They were housed in I I huts in one compound which had a tennis court, garden, canteen, mess hall and wash house. They settled in well and found the facilities satisfactory' An internees' committee was formed and Tsutsumi was chosen as compound leader. He sent a telegram to Woodmans Point Camp on 29 January 1942: Arrived safely Saturday evening without troubles and all of us are in good health but much colder and windy than expected. Desires all your side are in good health. Pass your time pleasantly. Kindest regards. I On 31 January, however, they were informed that they were to be moved to an eastern state, and on 1 February 195 unattached men left for Loveday. On 8 February Tsutsumi wrote: It has just been two months since we were interned. We have been told that family groups are to travel by rail to the East. The exact destination is still unknown ... There is not much else to talk about. We chatted about what is going to happen to us over a period of time over a cup of tea and the cakes which our dear Italian friends baked for us. The internees at Harvey had access to local newspapers and Mine idea of how the

The policeman told us to pack up things, a change of clothes and things ... We were put in a tent at the Broome gaol. The gaol was already packed with the Japanese. We slept in the tent for one night and the next day we were taken on a ship ...69 Yoshi Kanegae, an Australian-born of Japanese-Aboriginal origin, was neither upset nor afraid of being arrested. She said: "Dad was in and Auntie was in ... so I was excited to go and looking forward to seeing them again."' At noon on 19 January the "Koolinda" left Broome carrying 212 Japanese internees, picked up thirty-four Japanese internees at Port Hedland, Point Samson, Onslow and Carnarvon, and arrived at Fremantle on 24 January.71 The internees were divided into two groups—the family groups being taken to Woodmans Point Internment Camp, and the men to Harvey Internment Camp.72 Harvey was about 100 kilometres south of Perth. The men arriving there were given a friendly welcome by Italian internees. They were housed in I I huts in one compound which had a tennis court, garden, canteen, mess hall and wash house. They settled in well and found the facilities satisfactory' An internees' committee was formed and Tsutsumi was chosen as compound leader. He sent a telegram to Woodmans Point Camp on 29 January 1942: Arrived safely Saturday evening without troubles and all of us are in good health but much colder and windy than expected. Desires all your side are in good health. Pass your time pleasantly. Kindest regards.74 On 31 January, however, they were informed that they were to be moved to an eastern state, and on 1 February 195 unattached men left for Loveday. On 8 February Tsutsumi wrote: It has just been two months since we were interned. We have been told that family groups are to travel by rail to the East. The exact destination is still unknown ... There is not much else to talk about. We chatted about what is going to happen to us over a ow of tea and the cakes which our dear Italian friends baked for us. The internees at Harvey had access to local newspapers'

tune.-"

'Jut good enough top lay a simple

The Japanese teachers forbade popular Japanese songs: only military and children's songs were sung.' Saburoo Kanegae from Broome, who was eleven in 1946, learnt a military song called "Umi Yukaba" [Going Over the seal at the school: At sea be my body water-soaked, On land be it with grass overgrown, Let me die by the side of my Sovereign! Never will I look back."

Mari Kai, from New Caledonia, was a student at the school. She talked about her teacher, Mori: He was a very strict teacher. I only knew a few words of Japanese when I first went to the camp school. I used to speak French with my friends from New Caledonia ... He hit me on the head when I spoke French at school.' Sullivan wrote about Mori: "Mori sure was strict. We had nothing on hist' in and some of the others?' The curriculum was decided on by the teachers and committees and reflected the ideology of nationalism and militarism prescribed for elementary schools in Japan.' The textbooks were written by the teachers and included reading passages generally of patriotic nature. By 1945 Mari was able tc read advanced Japanese from Volume 12. The first lessor consisted of poems by the Emperor Meiji, such as: booking at pages from the past, how is my land now? I wish my mind was as vast and clear as the blue sky.

Although he was released the same day as he was a natura-born British subject, he was taken in again a week later

I was picking; up passengers from the icily arid Sgt, Cowic c;Jrne u and said, "I wain yoti apain," pack(.(1 my stuff and they put nip in gaol again. I cou (In I. do anything My wii(:; ;Ind '/)fl stiJ here in Broome and my business was .just left sitting On 21 December the internees were told that they were to be transferred south. By this date 185 had been detained:4 On 22 December a prisoners' committee was set up in the Broome gaol to organise welfare matters. Approaching New Year, the Committee debated whether it could display the Emperor's picture for the New Year celebration in a gaol. Those against were in the majority, and the New Year events took place without the Emperor's portrait. The internees celebrated the New Year as best they could in the gaol and enjoyed special Japanese food prepared for the occasion. Some later enjoyed a game of mah... pr jong.67 On 18 January the Japanese were taken by trucks to board the "Koolinda". On the previous day, Australian-born. wives and Children had been taken into custody. The Shiosaki family was included. Alf Shiosaki was ten: I can't remember exactly when, but one day I was outside with Dad and saw the aurora fsid. Dad said, "Waes coming." And one day sometime after that, a truck came and took us ... we were having lunch then, had to leave everything behind ...68 Alf's older sister, Peggy, also remembers the day. In her home in Derby, she said:

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

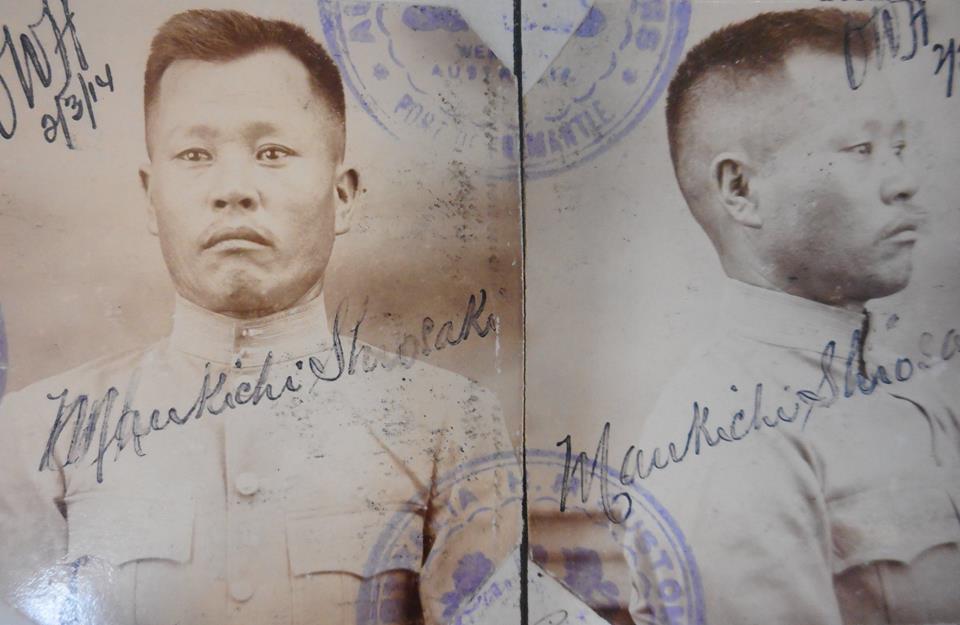

An Aboriginal Japanese family: the Shiosakis

JAPANESE GO NORTH AGAIN

Although resident for many years in the north-west of this State, Japanese were interned for the duration of the war. Yesterday the Shiosaki family of nine and Kotsukyo Nomura (left) returned to this State by train. They will sail shortly by the Koolinda, the Shiosaki family for Broome, where they will reopen their laundry, and Nomura, a pre-war shopkeeper in Carnarvon, for Onslow to become a station cook.From left to right. Kotsukyu Nomura, Alf Shiosaki, Stella Gibson, Peggy Carlisle, Charles Shiosaki, Margaret Shiosaki nee Beasley.

2nd Row

Cyril Shiosaki, Ronald Shiosaki, Maurice Shiosaki & Ben Shiosaki. The last daughter is Irene Nannup. (West Australian Newspaper 3.12.1946 p.8)

Maurice Shiosaki

Born: Broome, 1939

Interned: Tatura (Victoria), 1941–46

As a boy interned at Tatura in Victoria, part-Japanese, part-Aboriginal Maurice and his older brothers made kites to pass the time. Standing in the barbed-wire enclosure of the family camp, they released their kites and watched them soar high above them. ‘We used to make our own kites out of bamboo and the paper that apples used to be wrapped in. We made glue out of flour and water. We used sewing cotton for the string.

The older boys used to crush light globes into a powder and mix flour and water in, run the mixture along the string and then dry it out. Then we’d fly our kite,and the boys from the other compounds used to fly theirs—so we’d be standing in different compounds—and we’d go voom! To try to cut their string. That was kite fighting—it was all friendly, though’. Kite fighting was one of many activities Maurice did during the five years he was interned, from the age of two to seven. He also recalls taking part in sumo matches against other kids and occasionally being treated to picnics outside camp grounds. ‘I remember eating hot dogs. We used to go in army trucks out to this lake. It was a nice area—a lot of wildlife. They had big containers to boil hot dogs in.’

The Shiosakis were a family of eight children, so there was never a shortage of playmates for Maurice, who remembers his time at camp fondly. ‘We were treated very well, as far as I can remember… All the time we were there, we were very happy.’ Maurice spent so much time socialising with the other Japanese kids at camp that his Japanese became better than his English. ‘I could talk Japanese A-1 until I left the camp… [But] I’ve forgotten it all now.’

But the family experienced hardship in other ways. Maurice’s father, Shizuo, owned a laundry business in Broome, but when war broke out with Japan he

was forced to abandon it. ‘They said, “Pack your things up, you’re going.” That was it… [My father] lost everything,’ Maurice said. When the family was finally released from internment in 1946, they had to start afresh. Maurice’s father found work in Perth doing the laundry at Clontarf Boys Town, then later in Mullewa (WA) working on the railway.

On the day of their release from internment, the Shiosakis farewelled the life they had known for five years and the people they had shared it with. Many of their friends were being sent to Japan against their wishes as, according to government policy, Japanese who weren’t married to British subjects or who didn’t have Australian-born children couldn’t stay in Australia (Nagata 1996, p. 193). ‘The saddest part of all our time at camp was when it was time to leave,’ Maurice said.‘There were rows and rows of army trucks the day we started to move out. Everyone was crying. Everyone was clinging to the fence.’

Oyuki Shiosaki in 1929.

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

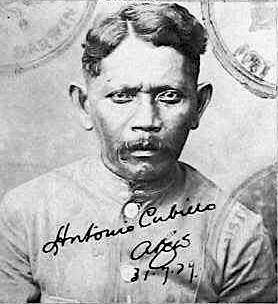

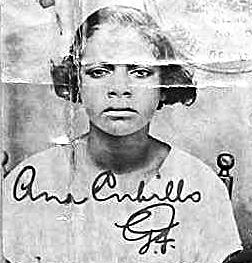

An Aboriginal Philipino family: theCubillos

DRAFT subject to approval from the elders of this family

resource material only not yet, written by me:

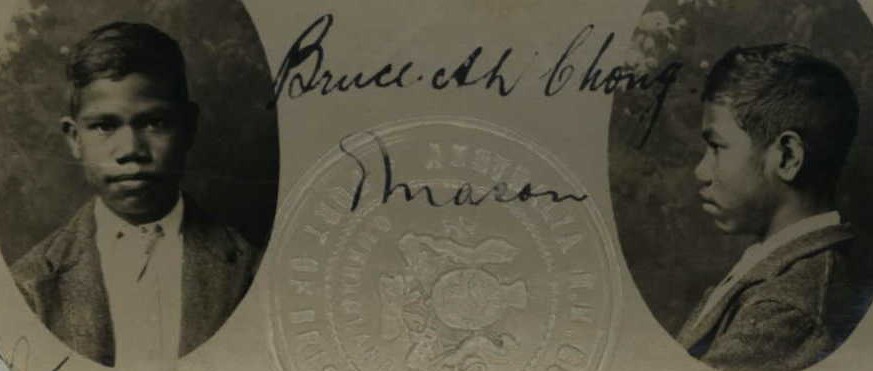

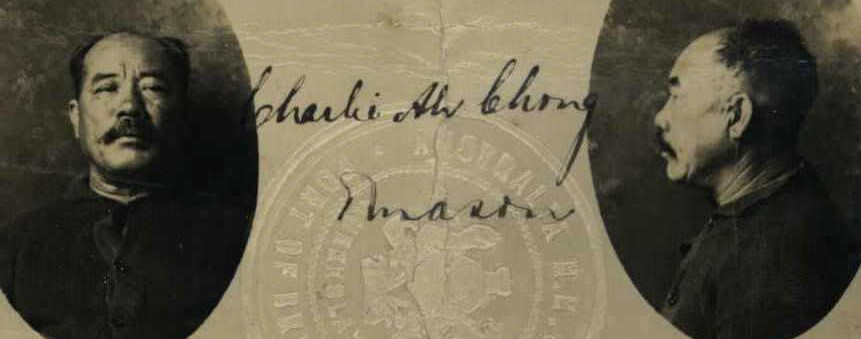

Bruce Ah Chong,11, student, travelled with his father Charlie Ah Chong, 56, a storekeeper at Camooweal, in 1924 and returned in 1929. His indigenous mother died soon after his birth at Burketown in the Gulf country of Queensland.